Frequently Asked Questions

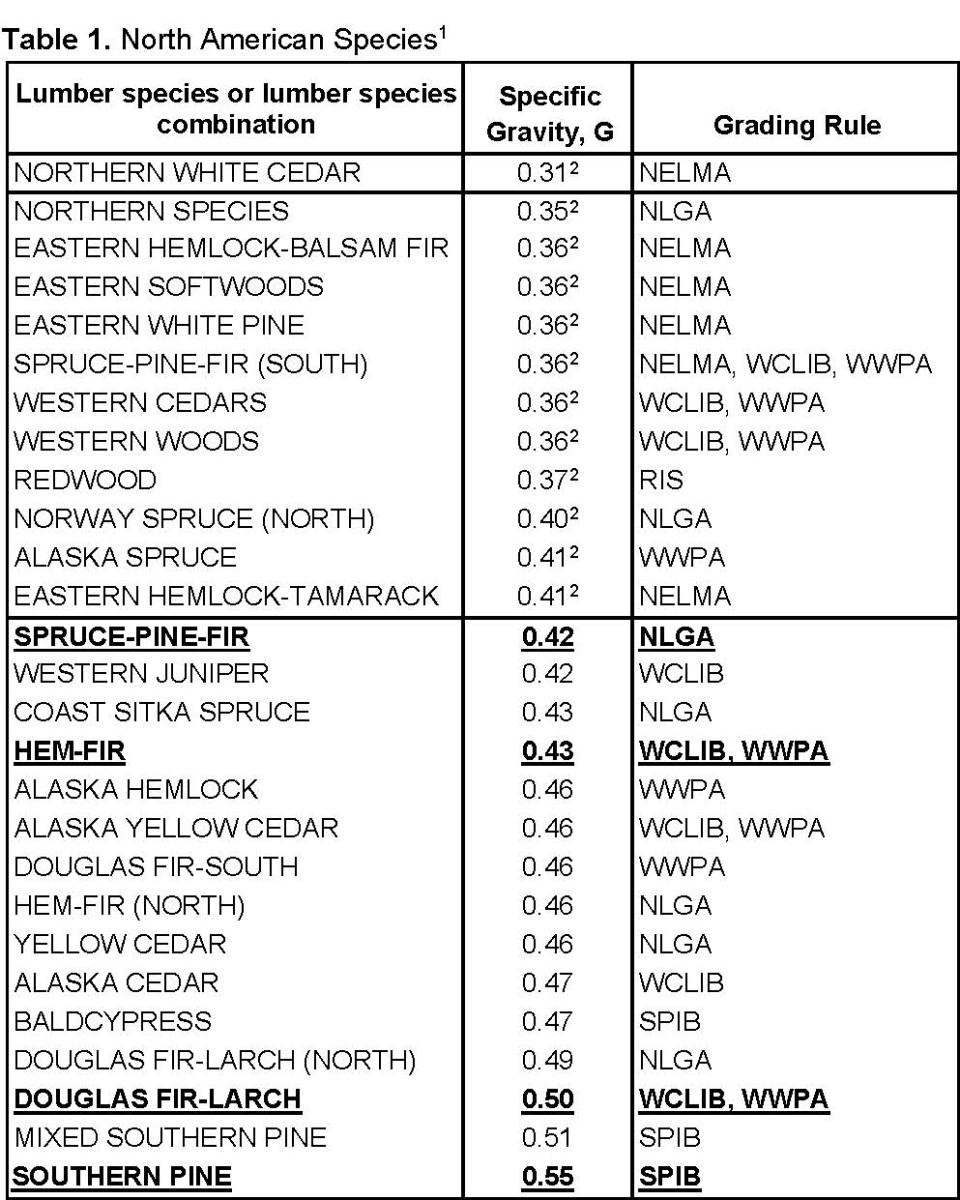

See Tables 1 and 2 for visually graded lumber species and lumber species combinations and assigned specific gravity per the National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction. Assigned specific gravity in the NDS is an average property based on weight and volume when oven-dry. Bold entries are commonly available lumber species combinations used in International Residential Code and International Building Code span tables for joists and rafters.

- For a complete listing of lumber species, lumber species combinations and assigned specific gravity, see NDS Supplement Chapter 4 and its Addendum/Errata.

- Lumber with specific gravity less than 0.42 may be associated with special prescriptive fastening requirements in accordance with the International Residential Code (IRC) and International Building Code (IBC). Bold entries are commonly available lumber species combinations used in IRC and IBC span tables for joists and rafters.

- For a complete listing of lumber species, lumber species combinations and assigned specific gravity, see NDS Supplement Chapter 4 and its Addendum/Errata.

- Lumber with specific gravity less than 0.42 may be associated with special prescriptive fastening requirements in accordance with the International Residential Code (IRC) and International Building Code (IBC).

A list of lumber grading rules writing organizations certified by the American Lumber Standards Committee (ALSC) is provided below.

- NELMA. Standard Grading Rules for Northeastern Lumber; published by the Northeast Lumber Manufacturers Association (NELMA), 272 Tuttle Road, P.O. Box 87A, Cumberland Center, ME 04021; 207.829.6901; 207.829.4293 (fax); e-mail [email protected]

- RIS. Standard Specifications for Grades of California Redwood Lumber; published by the Redwood Inspection Service (RIS), 1500 SW First Avenue, Portland Oregon 97204-2122; 503.224.3930; 503.224.3934 (fax); e-mail [email protected]

- SPIB. Standard Grading Rules for Southern Pine; published by the Southern Pine Inspection Bureau (SPIB), 4555 Spanish Trail, Pensacola, FL 32504; 850.434.2611; 850.434.1290 (fax); e-mail [email protected]

- PLIB/WCLIB. Standard Grading Rules for West Coast Lumber; published by the Pacific Lumber Inspection Bureau (PLIB/WCLIB); 1010 South 336th Street, Suite 210, Federal Way, WA 98003; 253.835.3344; 253.835.3371 (fax); e-mail [email protected]

- WWPA. Western Lumber Grading Rules; published by Western Wood Products Association (WWPA); 1500 SW First Avenue, Portland Oregon 97204-2122; 503.224.3930; 503.224.3934 (fax); e-mail [email protected]

- NLGA. Standard Grading Rules for Canadian Lumber; published by the National Lumber Grades Authority (NLGA); Suite 303 – 409 Granville St., Vancouver, BC V6C 1T2; 604.673.9100; 604.673.9141; e-mail [email protected]

For the most up to date information see:

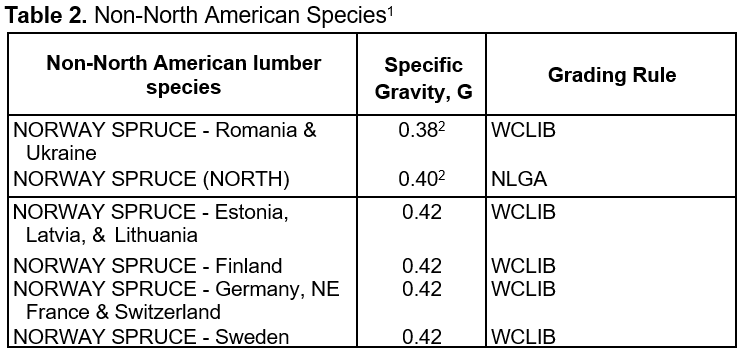

With few exceptions, lumber species or lumber species combination (usually in abbreviated form) is a standard component of lumber grade stamps per the American Lumber Softwood Lumber Standard – PS20.

These grade mark components are illustrated below for Visually Graded Lumber.

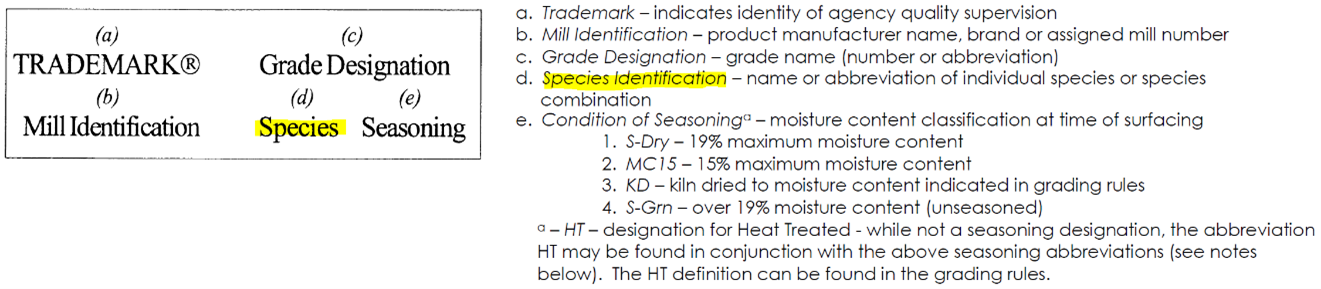

An example grade stamp for S-P-F (or Spruce-Pine-Fir) lumber species combination is shown below:

If lumber species or lumber species combinations questions arise based on grade stamp notations, the inspection agency for this example (i.e., Pacific Lumber Inspection Bureau) should be contacted:

See (http://alsc.org/uploaded/LumberProgram_facsimile%20September%202021.pdf) for more information on grade stamps including inspection agency contact information.

Where can I obtain information on designing post frame structures (sometimes referred to as pole buildings or pole barns)?

1. Design values for poles (smaller at the top and buried) and piles (smaller at the bottom and driven) are in the 2005 NDS Chapter 6. Design values for poles and piles were moved to the NDS Supplement: Design Values for Wood Construction in the 2012 Edition.

2. Post-Frame Design Manual (Second Edition) to be published by the Technical & Research Committee of the National Frame Builders Association (NFBA).

NFBA

4840 Bob Billings Parkway

Lawrence, KS 66049-3862

Phone: (800) 557-6957

Local: (785) 843-2444

Fax: (785) 843-7555

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: NFBA (National Frame Building Association)

3. ASAE Post Frame Building Manual

ISBN: 0-929355-29-6

Phone: 800-695-2723

Fax: 269-429-3852

4. The Midwest Plan Service publishes a Structures and Environment Handbookwhich address gussets in section 406.5 under Wood Truss Design. The most recent edition is a 1987 Revised 11th Edition. For ordering information, visit

https://www-mwps.sws.iastate.edu/catalog/construction-farm/structures-and-environment-handbook

Midwest Plan Service

122 Davidson Hall

Iowa State University

Ames, IA 50011-3080

Toll Free: (800) 562-3618

E-mail: [email protected]

Design for Code Acceptance (DCA) #5 provides guidance to post-frame building designers for meeting the requirements of the 2000 International Building Code and to confirm that a properly designed post-frame building is in fact code compliant.

See also General FAQ: “Where can I find information on Timber Poles and Piles?”

See also General FAQ: “What is timber frame construction and where do I find more information about it?”

The Southern Forest Products Association (SFPA) publishes the Permanent Wood Foundations Design and Construction Guide. Download the document here.

AWC’s PWF Design Fabrication Installation (DFI) Manual and Technical Report #7, Permanent Wood Foundation System Basic Requirements (TR7) have both been discontinued and are out of print. ANSI / AWC PWF – Permanent Wood Foundation Design Specification replaces TR7 and has been adopted in the 2009/2012 International Residential Code and 2009/2012 International Building Code. This document primarily addresses structural design requirements. See the SFPA Permanent Wood Foundations Design and Construction Guide for construction details and tabulated data.

- Designing Retaining Walls, Bulkheads and Seawalls of Treated Timber. Author: American Wood Preservers Institute, 1966

- Earth Retaining Structures. Author: W.D. Keeney, AWPI

- Improved Standard Designs Pressure-Treated Timber Crib Walls. AWPI, 1969.

- Available upon e-mail request: [email protected].

Guidance for this issue can be found in the commentary to the Permanent Wood Foundation Design Specification. The PWF commentary states in C5.4.5:

- Since nominal unit shear capacities for shear walls and diaphragms published in the Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic (SDPWS) Specification are based on short-term load duration, it is necessary to multiply nominal unit shear capacities for seismic by 0.281. The 0.281 multiplier results from the combination of the 2.0 allowable stress design (ASD) reduction factor and a 0.9/1.6 factor for adjusting from the ten-minute load duration basis for wind and seismic design in the SDPWS to a permanent load duration basis for PWF applications.

Anchor bolt connections designed per SDPWS 4.3.6.4.3 are designed for the shear load in the sill plate. If the shear capacity of a double-sided shear wall is twice that of a single-sided shear wall, the anchor bolt spacing derived based on the anchor bolt shear capacity for a double-sided shear wall would be half the spacing of a single-sided shear wall. Staggering the anchor bolts 1/2″ from the plate edge for a double-sided shear wall provides uplift resistance on each edge of the sill plate equivalent to a single row of anchor bolts located 1/2″ from the plate edge on a single-sided shear wall.

The National Design Specification® (NDS®) Supplement tables list design values for 2x and larger decking.

The American Lumber Standards Committee (ALSC) provides a Policy for Evaluation of Recommended Spans for Span Rated Decking Products. Here’s more information on their website:

http://www.alsc.org/untreated_spanrated_mod.htm

You will need to contact the specific grading agencies to obtain their span ratings for various species. A list of those agencies is on the ALSC website as well.

Lateral design values for lumber diaphragms and shear walls are available in Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic.

See also General FAQ, “Where can I get span tables and span table information for lumber? Where can I get decking span tables?” for span information on decking.

Also see Tongue and Groove Roof Decking – WCD #2.

Also see Plank-And-Beam Framing for Residential Buildings – WCD #4.

AWC’s Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic, Table 4.2D contains shear capacities for lumber sheathing attached straight and diagonally. Table 4.3D contains shear wall capacities for straight and diagonal lumber sheathing as well.

AWC also publishes Plank and Beam Framing for Residential Buildings (WCD-4) (T14). It shows how this floor and roof framing system, traditionally used in heavy timber structures, can be adapted to home building.

The International Building Code contains design capacities for diagonally sheathed lumber diaphragms in section 2306.3 Wood Diaphragms. Visit http://www.iccsafe.org for ordering information.

Analysis Methods for Horizontal Wood Diaphragms by Jephcott and Dewdney from proceedings of a Workshop on Design of Horizontal Wood Diaphragms (ATC-7-1) conducted by Applied Technology Council on November 19-20, 1980 (25 pages). Visit their website at http://www.atcouncil.org/ to order.

Table 3.17D in the Wood Frame Construction Manual provides maximum shear wall segment aspect ratios for various wood and gypsum assemblies. Also see Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic Table 4.3.4. Typically, 3.5:1 is the maximum aspect ratio for design of blocked wood structural panel shear walls. For an 8′ tall shear wall, that would mean 27-1/2″ of full-height sheathing.

The segmented shear wall method considers each full-height segment individually, and has hold-downs at the ends of each full-height segment. The perforated shear wall method only requires hold downs at the very ends of the shear wall length. Both methods are covered in various AWC standards including Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic and the Wood Frame Construction Manual.

![]() Read the Perforated Shear Wall Design PDF for more information.

Read the Perforated Shear Wall Design PDF for more information.

Values of apparent shear stiffness, Ga, are tabulated in seismic columns of the SDPWS to facilitate calculation of seismic story drift in accordance with ASCE 7 Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures. Values of Ga are equally applicable for calculation of the shear deformation component of total deflection due to wind loads up to the ASD wind unit shear value calculated as vw/2.0. This level of unit shear for wind is identical to 1.4 times the ASD seismic unit shear capacity for which apparent shear stiffness values were originally developed (see SDPWS Commentary C4.2.2).

AWC Wood Frame Construction Manual (WFCM) 2015 Edition is presently referenced in model building codes such as the IBC (International Building Code) and IRC (International Residential Code). The WFCM is an ANSI-approved document that provides engineered and prescriptive requirements for wood frame construction based on dead, live, snow, seismic, and wind loads from ASCE 7-10 Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures.

AWC Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic (SDPWS) 2015 Edition is presently referenced in model building codes such as the IBC. The SDPWS is an ANSI-approved document that covers materials, design, and construction of wood members, fasteners, and assemblies to resist wind and seismic forces.

Wood has a high strength-to-weight ratio. Since wood is lighter than steel or concrete, there is less mass to move—a critical factor during an earthquake. Wood members connected with steel fasteners create a very ductile (flexible) assembly which is less prone to brittle failures often seen with unreinforced masonry or concrete structures.

Multiple, repetitive wood members (studs, joists, and rafters at 16”-24” on-center) provide redundancy in wood assemblies making them less prone to catastrophic collapse. Wood’s renewability, low life-cycle environmental impacts, and ability to sequester carbon provides the optimal combination of green building and stability for earthquake-prone areas.

Tests have proven the viability of wood frame structures under seismic loads.

For the perforated shear wall method, the internal vertical members are not designed to resist tension due to overturning; but for compression due to overturning the design force would be the same as would result from using a segmented shear wall method. See Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic and the Wood Frame Construction Manual.

![]() Read the Perforated Shear Wall Design PDF for more information.

Read the Perforated Shear Wall Design PDF for more information.

Guidance for this issue can be found in the commentary to the Permanent Wood Foundation Design Specification. The PWF commentary states in C5.4.5:

- Since nominal unit shear capacities for shear walls and diaphragms published in the Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic (SDPWS) Specification are based on short-term load duration, it is necessary to multiply nominal unit shear capacities for seismic by 0.281. The 0.281 multiplier results from the combination of the 2.0 allowable stress design (ASD) reduction factor and a 0.9/1.6 factor for adjusting from the ten-minute load duration basis for wind and seismic design in the SDPWS to a permanent load duration basis for PWF applications.

A splice is a means of connecting discontinuous top plate members to transfer the design tension force. For the design assumptions in the WFCM, all top plate joints must be spliced in order to maintain diaphragm chord tension capacity. See WFCM Table 3.21 for top plate splice requirements.

The following design standards for wood construction in high wind areas are presently referenced in model building codes such as the IBC (International Building Code) and IRC (International Residential Code):

1. AWC Wood Frame Construction Manual (WFCM) 2015 Edition

2. ICC Standard for Residential Construction in High Wind Regions (ICC-600)

The WFCM is an ANSI approved document that provides engineered and prescriptive requirements for wood frame construction based on dead, live, snow, seismic and wind loads derived from the ASCE 7-10 Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures.

ICC-600 presents prescriptive methods to provide wind resistant designs and construction details for residential buildings. The standard is an update to SSTD 10-99 and includes new provisions such as prescriptive designs for wind speeds up to 150 mph with three-second gusts and exterior wall coverings for high wind.

AWC’s Wood Frame Construction Manual (WFCM) for One- and Two-Family Dwellings prescriptively limits cantilevers based on the following conditions, where L is the length of the simple span, center to center of bearing and d is the depth of the joist:

Loadbearing wall, shear wall or non-shear wall <= d

Non-loadbearing, shear wall or non-shear wall <= L/4

Non-loadbearing shear wall <=4d

AWC’s Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic, Table 4.2D contains shear capacities for lumber sheathing attached straight and diagonally. Table 4.3D contains shear wall capacities for straight and diagonal lumber sheathing as well.

AWC also publishes Plank and Beam Framing for Residential Buildings (WCD-4) (T14). It shows how this floor and roof framing system, traditionally used in heavy timber structures, can be adapted to home building.

The International Building Code contains design capacities for diagonally sheathed lumber diaphragms in section 2306.3 Wood Diaphragms. Visit http://www.iccsafe.org for ordering information.

Analysis Methods for Horizontal Wood Diaphragms by Jephcott and Dewdney from proceedings of a Workshop on Design of Horizontal Wood Diaphragms (ATC-7-1) conducted by Applied Technology Council on November 19-20, 1980 (25 pages). Visit their website at http://www.atcouncil.org/ to order.

Table 3.17D in the Wood Frame Construction Manual provides maximum shear wall segment aspect ratios for various wood and gypsum assemblies. Also see Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic Table 4.3.4. Typically, 3.5:1 is the maximum aspect ratio for design of blocked wood structural panel shear walls. For an 8′ tall shear wall, that would mean 27-1/2″ of full-height sheathing.

AWC Wood Frame Construction Manual (WFCM) 2015 Edition is presently referenced in model building codes such as the IBC (International Building Code) and IRC (International Residential Code). The WFCM is an ANSI-approved document that provides engineered and prescriptive requirements for wood frame construction based on dead, live, snow, seismic, and wind loads from ASCE 7-10 Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures.

AWC Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic (SDPWS) 2015 Edition is presently referenced in model building codes such as the IBC. The SDPWS is an ANSI-approved document that covers materials, design, and construction of wood members, fasteners, and assemblies to resist wind and seismic forces.

Wood has a high strength-to-weight ratio. Since wood is lighter than steel or concrete, there is less mass to move—a critical factor during an earthquake. Wood members connected with steel fasteners create a very ductile (flexible) assembly which is less prone to brittle failures often seen with unreinforced masonry or concrete structures.

Multiple, repetitive wood members (studs, joists, and rafters at 16”-24” on-center) provide redundancy in wood assemblies making them less prone to catastrophic collapse. Wood’s renewability, low life-cycle environmental impacts, and ability to sequester carbon provides the optimal combination of green building and stability for earthquake-prone areas.

Tests have proven the viability of wood frame structures under seismic loads.

AWC’s Wood Construction Data #1 Details for Conventional Wood Frame Construction, which provides proper methods of construction in wood frame buildings, with information on features which contribute to the satisfactory performance of wood structures.

AWC publishes the Wood Frame Construction Manual for One- and Two-Family Dwellings to provide solutions based on engineering analysis, in accordance with recognized national codes and standards. Like conventional construction, the engineered solutions are provided in a prescriptive format.

The WFCM does not require special consideration of floor plan offsets up to 4′. If the floor plan offset exceeds 4′ deep, the provisions of 1.1.3.3a would apply. The building would be designed as:

1) separate structures attached at the wall line at the offset(s); or,

2) a rectangular building with perimeter dimensions that inscribe the entire structure including the offsets.

The appropriate design method would be decided by the complexity of the building shape and the load path required to transfer the forces.

The WFCM uses the envelope procedure, which is a simplified method where GCpf values are developed to provide maximum structural actions from boundary-level wind tunnel tests of low-rise buildings meeting certain limitations. The directional procedure uses GCp values that are based on general aerodynamic theory and is more generally applicable to all buildings.

Exposure B as defined in the WFCM and ASCE7-10 is as follows: “Urban and suburban areas, wooded areas, or other terrain with numerous closely spaced obstructions having the size of singe family dwellings or larger.”

Exposure C as defined in the WFCM and ASCE7-10 is as follows: “Open terrain with scattered obstructions including surface undulations or other irregularities having height generally less than 30 feet extending more than 1500 feet from the building site in any quadrant. Exposure C extends into adjacent Exposure B type terrain in the downwind direction for the distance of 1500 feet or 10 times the height of the building or structure, whichever is greater. This category includes open country and grasslands, and open water exposure for less than 1 mile.”

Exposure D as defined in the WFCM is as follows: “Flat unobstructed areas exposed to wind flowing over open water for a distance of a least 1 mile. This exposure shall apply only to those buildings and other structures exposed to the wind coming from over the water. Exposure D extends inland from the shoreline a distance of 1500 feet or 10 times the height of the building or structure, whichever is greater.” The ASCE7-10 definition is similar.

Exposure D is outside the scope of Chapter 3 of the WFCM. It would require either design using WFCM Chapter 2 or ASCE 7. Conversion factors for Exposure D are available in WFCM Table 2.1.3.1 and their applicability is noted in Chapter 2 Table footnotes.

Yes. For each wind direction, there can be a different exposure.

In the WFCM, Mean Roof Height is defined as “the distance from the average grade to the average roof elevation.” See WFCM Figure 1.2.

The WFCM is limited to a Mean Roof Height (MRH) of 33′ or less, but the envelope method in ASCE 7-10 that is used in the WFCM has a limit of 60′.

No. Portal frames are outside the scope of the WFCM.

There are currently no WFCM Excel, Mathcad, or other pre-programmed sheets for general use. There is an online span and connection calculator that can be accessed through the AWC website, www.awc.org. Also, WoodWorks Software includes a shear wall module that generates wind pressure and resulting diaphragm loads per ASCE 7-10.

The WFCM designs with exterior shear walls. If the building is broken into individual separate structures, there would be interior shear walls that extend to the roof diaphragm unless an alternative design is provided.

Yes. WFCM Section 3.2.6.1 requires ridge straps, but provides an exception for collar ties: “Ridge straps are not required when collar ties (collar beams) of nominal 1×6 or 2×4 lumber are located in the upper third of the attic space and attached to rafters in accordance with Table A-3.6.”

See the following article for more information:

http://www.jlconline.com/roofing/conventional-roof-framing-a-codes-eye-view_o.aspx

All roof and wall sheathing designs are based on 8d common or 10d box nails, regardless of sheathing type or thickness. Table 3.1 in the WFCM provides a complete nailing schedule.

For unblocked diaphragms, the blocking requirements for floor and roof diaphragm bracing to transfer wind loads from exterior walls into the floor/roof diaphragm are based on the number of bay spacings required to get the load into the floor and roof sheathing. See WFCM 3.3.5 and 3.5.5.

See WFCM section 3.5.1.3 for depth to thickness ratios requiring blocking. Shear transfer through rafter/ceiling joist to top plate connections is assumed to happen without blocking if depth-to-thickness ratios are in accordance with WFCM 3.5.1.3. This is for diaphragm capacities in accordance with WFCM chapter 3 requirements

Connectors should be detailed to align the uplift load on the same side of the stud avoiding cross grain bending in the top plate. See WFCM Figure 3.2k for an example.

From the WFCM Commentary: “Uplift for design of rafters, roof cladding, and roof sheathing attachment is calculated using Components and Cladding (C&C) loads. Uplift connections for roof assemblies are calculated using enveloped Main Wind Force-Resisting System (MWFRS) loads. The rationale for using MWFRS loads for computing the uplift of roof assemblies recognizes that the spatial and temporal pressure fluctuations that cause the higher coefficients for components and cladding are effectively averaged by wind effects on different roof surfaces consistent with the definitions of C&C and MWFRS loads in ASCE 7. Also note that C&C loads are used to calculate wall bending loads whereas MWFRS loads are used to calculate combined bending and axial loads. Within the scope of the WFCM, C&C bending loads control.” See the following paper for more details:

Considerations in Wind Design of Wood Structures ![]()

Yes. See WFCM 3.2.6.1 for ridge connection requirements.

Yes. WFCM Section 3.4.4.2.3 allows a single hold-down to be used to resist overturning forces in both directions where full height shear wall segments meet at a corner, provided the corner framing in the adjoining walls is adequately fastened to transfer the load.

WFCM 2.1.3.3a allows loadbearing walls to be 20′ in height, but requires engineering analysis. WFCM 3.1.3.3a limits prescriptively designed loadbearing wall heights to 10′ and non-loadbearing wall heights to 20′.

If you are asking about mechanical connectors, that is a question for the connector manufacturer. For multiple fasteners and/or fastener types, there are specific design requirements (see NDS 10.1.4 and 10.2.2). In general, capacities of different fastener types cannot be directly summed.

WFCM 2.1.3.4d and 3.1.3.4d limits the maximum roof slope to 12:12.

Yes. WFCM Section 3.2.6.1 requires ridge straps, but provides an exception for collar ties: “Ridge straps are not required when collar ties (collar beams) of nominal 1×6 or 2×4 lumber are located in the upper third of the attic space and attached to rafters in accordance with Table A-3.6.”

No. For lateral stability of floor joists and rafters, blocking requirements are based on the d/b ratio. See WFCM 3.3.1.4 and 3.5.1.3.

In the WFCM, the total load on a sloped roof has been tabulated in terms of vertical projection and horizontal dimensions.

We do not have any examples. TPI may have details.

When rafters have a pitch greater than 12:12, they behave more like beam-columns, where the member takes both axial and bending loads. This scenario is not considered in prescriptive rafter design tables and calculations.

Unless otherwise stated, all calculations are based on Allowable Stress Design (ASD) load combinations using loads from ASCE 7-10 Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures. For wind, ASCE 7-10 calculations are based on 700-year-return-period “three-second gust” wind speeds between 110 and 195 mph. Snow loads are designed in accordance with ASCE7-10 for buildings in regions with ground snow loads between 0 and 70 psf. Both balanced and unbalanced snow load conditions are considered in design.

Use of staples for shear walls and diaphragms would be at the discretion of the code official.

The scope of the WFCM in Chapter 1 states it can be used for Exposures B, C, and D; however, Chapter 3 limits the scope for the prescriptive chapter to Exposures B and C. If you need to design for Exposure D, you will need to do it per WFCM Chapter 2 in accordance with appropriate table footnotes.

A dropped header is a header that is installed below the roof or floor framing with a short wall (knee wall or cripples) between the header and the top plate. Under some “dropped” conditions, a header may be assumed to be fully-braced and a design reduction does not need to be applied to account for buckling, which will allow for a longer span than a raised header condition.

The WFCM defines a rafter tie as a structural framing member located in the lower third of the attic space that ties rafters together to resist thrust from gravity loads on the roof. The WFCM defines a collar tie as a structural member located in the upper third of the attic space that ties rafters together to resist separation of the tops of the rafters due to uplift in a ridge board configuration. Ceiling joists or rafter ties resist outward thrust of the rafters in the lower third of the attic space. See WFCM Figures 3.10b-c. See WFCM 3.2.6.1 for ridge connection requirements.

If there are no rafter ties or ceiling joists (or if the rafter ties or ceiling joists aren’t adequately attached to the rafters), the roof framing must be constructed using a ridge beam so the rafters do not impose an outward thrust at the top of the wall.

NDS Archives + Historical Design Values

1991-1997 NDS Commentary – Historical Development

Wood Handbook – Wood as an Engineering Material

Wood and Timber Condition Assessment Manual, Second Edition – Electronic (PDF)

by Robert J. Ross and Robert H. White

Here’s contact information for the lead author:

Dr. Robert J. Ross

Email: [email protected]

Phone: (608) 231-9221

Website: http://www.fs.fed.us/research/people/profile.php?alias=rjross

Other resources:

Evaluation, Maintenance and Upgrading of Wood Structures: A Guide and Commentary. Published by: ASCE (Proceedings of a session at Structures Congress, 1986). Edited by: Alan Freas. Available at https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=6lghAGA7OLwC

Evaluation and Upgrading of Wood Structures: Case Studies. Published by: ASCE (Proceedings of a session at Structures Congress, 1986). Edited by: Vijay K. A. Gopu. Available at http://cedb.asce.org/CEDBsearch/record.jsp?dockey=0050270

ISBN # 0872625508

Grading of existing timbers

West Coast Lumber Inspection Bureau (WCLIB) will grade existing timbers. Here’s contact information:

WEST COAST LUMBER INSPECTION BUREAU

PO Box 23145

Portland, Oregon 97281-3145

503-639-0651

Fax: 503-684-8928

http://www.wclib.org/

Historical Considerations in Evaluating Timber Structures

R. L. Tuomi and R. C. Moody, Engineers

Forest Products Laboratory U.S. Department of Agriculture

http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplgtr/fplgtr21.pdf

Fire and Smoke Repair

Restoration Industry Association Guidelines for Fire & Smoke Damage Repair, 2nd Edition

Classic texts online

Rankin, William John MacQuorn (1866): Useful Rules and Tables Relating to Mensuration, Engineering, Structures, and Machines, Charles Griffn and Company, London, UK.

Includes timber design properties (see p. 199).

Johnson, J.B. (1904): The Materials of Construction – A Treatise for Engineers on the Strength of Engineering Materials, Fourth Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA.

Comprehensive strength of materials text for typical materials of the time, including timber (see p. 236-238).

Ketchum, Milo S. (1918): Structural Engineers Handbook – Data for the Design and Construction of Steel Buildings and Bridges, Second Edition, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc., New York, USA.

Includes timber Bridges and trestles (see p. 298).

Jacoby, H.S. (1909): Structural Details or Elements of Design in Timber Framing, John Wiley & Sons, NY, USA.

An early authoritative text on timber detailing, joints, connections, design, and more.

Common board grades (less than 2″ thick) used for decking or sheathing do not typically reflect design values for the lumber. When design values are required for boards used in design, stress-rated boards of nominal 1”, 1-1/4”, and 1-1/2” thickness, 2” and wider, of most species, are permitted to use the design values shown in the NDS Supplement for Select Structural, No. 1 & Btr, No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, Stud, Construction, Standard, Utility, and Clear Structural grades as shown in the 2” to 4” thick categories, when graded in accordance with the stress-rated board provisions in the applicable grading rules. Information on stress-rated board grades applicable to the various species is available from the respective grading rules agencies. See NDS Supplement Table 1B, footnote 1 and NDS Supplement Tables 4A and 4B, footnote 2 for more information.

With assistance from AWC, a report on anchor bolts connecting wood sill plates to concrete with edge distances typically found in wood frame construction is complete and available.

National Design Specification for Wood Construction (Publication #T-01) – Nationally recognized design guide for wood structures. Includes general requirements, design provisions and formulas, and data on structural connections (nails, bolts, screws, split ring, and shear plate connectors, and timber rivets).

The NDS Commentary provides background on development of NDS design provisions for bolt, lag screw, wood screw, nail, split ring, shear plate, and timber rivet connections.

Creep is the time-dependent deformation of loaded member undergoing elastic deformation.

The National Design Specification for Wood Construction (NDS) addresses creep in section 3.5.2-Long Term Loading. Under long term loading, the expected (average) deflection would be 1.5 times the initial deflection for seasoned lumber and 2.0 times the initial deflection for unseasoned lumber. Long term loading will cause a permanent set of about 1/2 the creep deflection.

The creep deflection varies anywhere from zero to twice the initial deflection. This means that the total deflection can vary from the initial deflection to as much as three times the initial deflection.

Forest Products Laboratory’s Wood Handbook – Chapter 4: Mechanical Properties of Wood

The NDS Supplement provides design values for Bald Cypress.

The National Design Specification® (NDS®) Supplement tables list design values for 2x and larger decking.

The American Lumber Standards Committee (ALSC) provides a Policy for Evaluation of Recommended Spans for Span Rated Decking Products. Here’s more information on their website:

http://www.alsc.org/untreated_spanrated_mod.htm

You will need to contact the specific grading agencies to obtain their span ratings for various species. A list of those agencies is on the ALSC website as well.

Lateral design values for lumber diaphragms and shear walls are available in Special Design Provisions for Wind and Seismic.

See also General FAQ, “Where can I get span tables and span table information for lumber? Where can I get decking span tables?” for span information on decking.

Also see Tongue and Groove Roof Decking – WCD #2.

Also see Plank-And-Beam Framing for Residential Buildings – WCD #4.

Shear parallel to grain (Fv) values along with compression perpendicular to grain (Fc?), bending (Fb), tension parallel to grain (Ft), compression parallel to grain (Fc), and modulus of elasticity (E) values are located in the NDS supplement, Design Values for Wood Construction.

Chapter 5 of the NDS contains design information for glued-laminated timber.

Model building codes recognize finger-jointed lumber for the same structural applications as solid sawn lumber with certain qualifications.

AWC’s code adopted National Design Specification® (NDS®) for Wood Construction, which specifies finger jointed lumber as having the same design values as solid sawn lumber.

From Chapter 4 of the 2005 NDS:

4.1.2.1 When the reference design values specified in the NDS are used, the lumber, including end-jointed or edge-glues lumber, shall be identified by the grade mark of, or certificate of inspection issued by, a lumber grading or inspection bureau or agency recognized as being competent (see Reference 31). A distinct grade mark of a recognized lumber grading or inspection bureau or agency, indicating that joint integrity is subject to qualification and quality control, shall be applied to glued lumber products.

4.1.6 Reference design values for sawn lumber are applicable to structural end-jointed or edge-glued lumber of the same species and grade. Such use shall include, but not be limited to light framing, studs, joists, planks, and decking. When finger jointed lumber is marked “STUD USE ONLY” or “VERTICAL USE ONLY” such lumber shall be limited to use where any bending or tension stresses are of short duration.

The NDS is referenced in all major model building codes in the U.S.

To obtain a copy of the NDS, which is part of the 2005 Wood Design Package, call the AWC publications department at 1-800-890-7732 or visit the website.

Grade Rules

End-joined lumber can be manufactured in different ways. Finger-joints or butt-joints are typical methods of joinery. The standards under which finger-jointed lumber is manufactured are the grading rules for end-joined pieces. These grade rules are promulgated like any other lumber grade rule and are ultimately reviewed by and approved by the American Lumber Standard Committee (ALSC). Finger joints for use in structural applications bear the grade stamp of an agency certified and approved by the Board of Review of ALSC.

Adhesives

ALSC recently modified its Glued Lumber Policy to add elevated-temperature adhesive performance requirements for end-jointed lumber intended for use in fire resistance-rated assemblies. End-jointed lumber manufactured with an adhesive which meets these new requirements is being designated as “Heat Resistant Adhesive” or “HRA” on the grade stamp. End-jointed lumber manufactured with an adhesive not tested or not qualified as a Heat Resistant Adhesive will be designated as “Non-Heat Resistant Adhesive” or “non-HRA” on the grade stamp, and will continue to meet building code requirements when used in unrated construction.

Adhesives used in finger-jointed lumber are of two basic types, depending on whether they are to be used for members with long duration bending loads like floor joists or short duration bending and tension loads like wall studs. Wood products using both types of adhesives have undergone extensive testing by manufacturers. Glued connections in products using the first adhesive type, containing phenolic resins, are sometimes referred to as “Structural Finger Joint,” and typically can be found in structural panels and glued-laminated timber. These products may be used interchangeably with solid sawn lumber in terms of strength and end use, including vertical or horizontal load applications. The second type of adhesive, typically containing polyvinyl compounds, is used with products that are then marked “VERTICAL USE ONLY” or “STUD USE ONLY.” These wood products may be used interchangeably with solid sawn lumber in terms of strength and are intended for applications where bending and tension stresses are of short duration, such as typically found in stud walls.

Does gypsum board provide lateral support to a wall stud assembly—to prevent it from buckling about the weak axis due to axial loads, and also to ensure that it is fully braced for bending when subjected to lateral loads?

The following references may be helpful in this regard:

RE: AXIAL LOADS

From the 1997 NDS® Commentary (Clause 3.6.7 – Lateral Support of Arches, Studs and Compression Chords of Trusses). Last paragraph (page 37) states:

“Use of the depth of the stud as the least dimension in calculating the slenderness ratio in determining the axial load-carrying capacity of normally sheathed or clad light frame wall systems also is long standing practice. Experience has shown that any code allowed thickness of gypsum board, hardwood plywood, or other interior finish adequately fastened directly to studs will provide adequate lateral support of the stud across its thickness irrespective of the type or thickness of exterior sheathing and/or finish used.”

From the 2001 NDS (Appendix A Clause A.11.3):

“When stud walls in light frame construction are adequately sheathed on at least one side, the depth, rather than breadth of the stud, shall be permitted to be taken as the least dimension in calculating the l_e/d ratio. The sheathing shall be shown by experience to provide lateral support and shall be adequately fastened.”

RE: LATERAL (BENDING) LOADS

From the 2001 NDS (Clause 4.4.1 Stability of Bending Members):

Clause 4.4.1.2 provides the following limits on the nominal depth-to-breadth ratios (d/b) for sawn lumber in order to use C_L = 1.0.:

“(a) d/b less than or equal to 2; no lateral support shall be required.

(b) 2 < d/b and less than or equal to 4; the ends shall be held in position, as by full depth solid blocking, bridging, hangers, nailing, or bolting to other framing members, or other acceptable means.

(c) 4 < d/b and less than or equal to 5; the compression edge of the member shall be held in line for its entire length to prevent lateral displacement as by adequate sheathing or subflooring, and ends at points of bearing shall be held in position to prevent rotation and/or lateral displacement.”

More requirements are also specified for greater d/b ratios; however, for wood studs, the range noted above should be adequate. For example, the d/b ratio for a 2×4 stud is (4/2 = 2), for a 2×6 stud is (6/2 = 3). Given these ratios, for pure bending, all that is required is that the ends be held in position.

RE: COMBINED BENDING AND AXIAL LOADS

Clause 4.4.1.3 also states:

“If a bending member is subjected to both flexural and axial compression, the depth to breadth ratio shall be no more than 5 to 1 if one edge is firmly held in line….”

So if the interior stud wall is sheathed with gypsum on both sides and is subjected to combined axial and lateral loads, for typical stud dimensions such as a 2×4 and 2×6, which result in relatively low d/b ratios (lower than 5), Clause 4.4.1.3 would suggest that a C_L = 1.0 could be used as well.

Changes in the 1991 NDS to dimension lumber design values are based on a comprehensive testing program conducted by the North American forest products industry called In-Grade Testing. Here’s an excerpt from section 4.2.3.2 of the NDS Commentary:

“The testing program conducted over an eight year period, involved the destructive testing of 70,000 pieces of lumber from 33 species groups. A new test method standard, ASTM D4761, was developed to cover the mechanical test methods used in the program. A new standard practice, ASTM D1990, was developed to codify procedures for establishing design values for visually graded dimension lumber from test results obtained from in-grade test programs.”

There are also a couple of 5-6 page articles on the subject:

“Lumber Design Values from In-Grade Test Results,” Wood Design Focus, Volume 2, No. 2, 1991, Forest Products Society.

“In-Grade: What it means,” Western Wood Products Association, Rev. 12-94.

In addition to these references, the Wood Handbook (Chapter 7), published by the Forest Products Lab, deals with lumber stress grades and derivation of design properties. It gives a good overview of the development of “small-clear” design values and “in-grade.” It also provides some additional references for further study.

Link to Chapter 7 on the FPL website

Note that concurrent with development of new design values in the 1991 NDS, behavioral equations for column, beam, and beam-column design also changed as a result of the In-Grade Testing program. Therefore, an advisory was issued with the 1991 NDS indicating that new design values were to be used simultaneously with new design equations and pre-1991 design values be used with pre-1991 design equations.

Design provisions and design values in the National Design Specification® for Wood Construction (NDS®) are applicable to lag screws conforming to ANSI/ASME Standard B18.2.1-1981. Tabulated design values are based on lag screws conforming to ANSI/ASME Standard B18.2.1-1981 and having assumed bending yield strengths provided in the table footnotes. Note that self-tapping lag screws are not addressed in ANSI/ASME B18.2.1 and are not specifically covered by provisions of the NDS. Specifically, the NDS does not address fabrication and assembly requirements, withdrawal design values, or lateral design values for self-tapping lag screws.

For self-tapping lags screws with dimensions similar to those provided in ANSI/ASME B18.2.1, the general form of the yield equations should apply for determining lateral design values. Accordingly, tabulated design values would also apply provided that the self-tapping lag screw dimensions meet or exceed the dimensions ASME B18.2.1 and the bending yield strength equals or exceeds the assumed bending yield strength in the table footnotes. In order to use lateral design provisions of the NDS, it must be assumed that fabrication and assembly of connections using self-tapping screws permits the development of the full bearing strength of the wood beneath the lag screw or permits yielding of the lag screw (i.e. installation does not damage the wood member or connection).

Finally, it should be noted that NDS Section 7.1.1.4 indicates that connections, other than those covered in the provisions, are not precluded from use where it is demonstrated by analysis, tests, or extensive experience that the connections will perform satisfactorily in their intended end use.

Full diameter screws have a larger unthreaded portion than the root diameter. Reduced diameter body screws’ shank portion is the same as the root diameter of the screw. See the figure in Table L2 (also below) of the 2005 NDS for more clarification.

The reason the root diameter was used in the 2005 NDS was to better address the use of “reduced body diameter” lag screws (vs. “full body diameter”)—and to better address the condition where the full length of the fastener is threaded.

Because “reduced body diameter” lag screws have a shank diameter approximately equal to the root diameter of “full body diameter” lag screws, design values for these fasteners are smaller than those provided in the 1997 NDS edition for “full body diameter” lag screws.

Root diameter (Dr), rather than the shank diameter, is used to calculate the tabulated lag screw design values, such as the ones shown in Table 11J.

Please refer to Section 11.3.6 Dowel Diameter in the 2005 NDS where it states:

“11.3.6.1 When used in Tables 11.3.1A and 11.3.1.B, the fastener diameter shall be taken as D for unthreaded full-body fasteners and Dr for reduced body diameter fasteners or threaded fasteners except as provided in 11.3.6.2…”

Where 11.3.6.2 states:

” 11.3.6.2 For threaded full body fasteners (see Appendix L), D shall be permitted to be used in lieu of Dr when the bearing length of the threads does not exceed 1/4 of the full bearing length in the member holding the threads…Alternatively, a more detailed analysis accounting for the moment and bearing resistance of the threaded portion of the fastener shall be permitted (see Appendix I).”

Design Aid 1 – Application of Technical Report 12 for Lag Screw Connections provides one alternate method of accounting for the moment and bearing resistance of the threaded portion of the fastener and moment acting along the length of the fastener as provided in Technical Report 12 (TR12) – General Dowel Equations for Calculating Lateral Connection Values.

The NDS Format Conversion Factor, KF, converts reference design values (allowable stress design values based on normal load duration) to LRFD reference resistances as described in ASTM D5457 Standard Specification for Computing Reference Resistance of Wood-Based Materials and Structural Connections for Load and Resistance Factor Design. The expression for KF is a constant divided by the resistance factor, Φ, and includes the following:

- a conversion factor to adjust an allowable design value to a strength level design value (embedded in the constant),

- a conversion factor to adjust from a 10-year (long-term) load duration to a 10-minute (short-term) load duration basis (embedded in the constant), and

- a conversion factor to adjust for a specified resistance factor, Φ (expressed independently in the denominator)

ASTM Standard F1667 Standard for Driven Fasteners: Nails, Spikes, and Staples provides dimensional tolerances. The National Design Specification (NDS) provides design values for common wire, box, or sinker nails.

1. ACI 318-02 Building Code Requirements for Structural

Concrete, American Concrete Institute,

Farmington Hills, MI, 2002.

Available at http://www.iccsafe.org.

2. ACI 530-99/ASCE 5-99/TMS 402-99 Building Code Requirements for Masonry Structures,

American Concrete Institute,

Farmington Hills, MI, 1999.

Available from the ASCE Bookstore.

3. AISI 1035 Standard Steels,

American Iron and Steel Institute,

Washington, DC, 1985.

4. ANSI Standard A190.1-2002, Structural Glued Laminated Timber.

APA – The Engineered Wood Association

http://www.apawood.org/

5. ANSI/ASCE Standard 7-02, Minimum Design Loads for

Buildings and Other Structures, American Society of Civil

Engineers, Reston, VA, 2003.

Available from the ASCE Bookstore.

6. ANSI/ASME Standard B1.1-1989, Unified Inch Screw

Threads UN and UNR Thread Form, American Society of

Mechanical Engineers, New York, NY, 1989.

Available from the ASME website.

7. ANSI/ASME Standard B18.2.1-1996, Square and Hex

Bolts and Screws (Inch Series), American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, NY, 1997.

Available from the ASME website.

8. ANSI/ASME Standard B18.6.1-1981 (Reaffirmed 1997),

Wood Screws (Inch Series), American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, NY, 1982.

Available from the ASME website.

9. ANSI/TPI 1-2002 National Design Standard for Metal Plate Connected Wood Trusses,

Truss Plate Institute, 2002.

Available from the Truss Plate Institute.

10.ASTM Standard A36-04, Specification for Standard Structural Steel, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2004.

Available from www.astm.org.

11. ASTM Standard A47-99, Specification for Ferritic Malleable Iron Castings, ASTM,

West Conshohocken, PA, 1999.

Available from www.astm.org.

12. ASTM A 153-03, Specification for Zinc Coating (Hot Dip) on Iron and Steel Hardware, ASTM,

West Conshohocken, PA, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

13. ASTM A 370-03a, Standard Test Methods and Definitions for Mechanical Testing of Steel Products, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

14. ASTM Standard A 653-03, Specification for Steel Sheet, Zinc Coated (Galvanized) or Zinc Iron Alloy Coated (Galvannealed) by the Hot Dip Process, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

15. ASTM Standard D 25-91, Round Timber Piles, ASTM,

West Conshohocken, PA, 1991.

Available from www.astm.org.

16. ASTM Standard D 245-00e1 (2002), Establishing Structural Grades and Related Allowable Properties for Visually

Graded Lumber, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2002.

Available from www.astm.org.

17. ASTM Standard D 1760-01, Pressure Treatment of Timber Products, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2001.

Available from www.astm.org.

18. ASTM Standard D 1990-00e1 (2002), Establishing Allowable Properties for Visually Graded Dimension Lumber from In-Grade Tests of Full Size Specimens, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2002.

Available from www.astm.org.

19. ASTM Standard D 2555-98e1, Establishing Clear Wood Strength Values, ASTM,

West Conshohocken, PA, 1998.

Available from www.astm.org.

20. ASTM Standard D 2899-95, Establishing Design Stresses for Round Timber Piles, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 1995.

Available from www.astm.org.

21. ASTM Standard D 3200-74(2000), Establishing Recommended Design Stresses for Round Timber Construction Poles, ASTM,

West Conshohocken, PA, 2000.

Available from www.astm.org.

22. ASTM Standard D 3737-03, Establishing Stresses for

Structural Glued Laminated Timber (Glulam), ASTM, West

Conshohocken, PA, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

23. ASTM Standard D 5055-04, Establishing and Monitoring Structural Capacities of Prefabricated Wood I Joists, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2004.

Available from www.astm.org.

24. ASTM Standard D 5456-03, Evaluation of Structural

Composite Lumber Products, ASTM, West Conshohocken,

PA, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

25. ASTM Standard D5764-97a (2002), Test Method for Evaluating Dowel Bearing Strength of Wood and Wood Base Products,ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2002.

Available from www.astm.org.

26. ASTM Standard D5933-96 (2001) , Standard Specification for 2-5/8 in. and 4 in. Diameter Metal Shear Plates for Use in Wood Construction, ASTM, West Conshohocken,PA, 2001.

Available from www.astm.org.

27. ASTM Standard F 606-02e1, Determining the MechanicalProperties of Externally and Internally Threaded Fasteners,

Washers, and Rivets, ASTM,

West Conshohocken, PA, 2002.

Available from www.astm.org.

28. ASTM Standard F1575-03, Standard Test Method for Determining Bending Yield Moment of Nails, ASTM, West

Conshohocken, PA, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

29. ASTM Standard F1667-03, Standard for Driven Fasteners:

Nails, Spikes, and Staples, ASTM, West Conshohocken,

PA, 2003.

Available from www.astm.org.

30. AWPA Book of Standards, American Wood Preservers’ Association, Granbury, TX, 2003.

Available from the AWPA store.

31. American Softwood Lumber Standard, Voluntary Product

Standard PS 20-99, National Institute of Standards and

Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, 1999.

Available at ALSC’s website.

32. Design/Construction Guide Diaphragms and Shear Walls,

Form L350, APA – The Engineered Wood Association,

Tacoma, WA, 2001.

Available from the APA.

33. Engineered Wood Construction Guide, Form E30, APA – The

Engineered Wood Association, Tacoma, WA, 2001.

Available from the APA.

34. Plywood Design Specification and Supplements, Form

Y510, APA – The Engineered Wood Association, Tacoma,

WA, 1997.

Available from the APA.

35. PS1-95, Construction and Industrial Plywood, United

States Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards

and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, 1995.

36. PS2-92, Performance Standard for Wood-Based Structural-

Use Panels, United States Department of Commerce, National

Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, 1992.

37. SAE J412, General Characteristics and Heat Treatment of

Steels, Society of Automotive Engineers, Warrendale, PA,

1995.

Available from the SAE website.

38. SAE J429, Mechanical and Material Requirements for Externally Threaded Fasteners, Society of Automotive

Engineers, Warrendale, PA, 1999.

Available from the SAE website.

39. Specification for Structural Joints Using ASTM A325 or

A490 Bolts, American Institute of Steel Construction

(AISC), Chicago, IL, 1985.

40.Specification for Structural Steel Buildings Allowable

Stress Design and Plastic Design, American Institute of

Steel Construction (AISC), Chicago, IL, 1989.

Available from the Tech Street Website.

41. Specification for the Design of Cold Formed Steel Structural

Members, American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI),

Washington, DC, 1996.

Available from http://www.steel.org

42. Standard Grading Rules for Canadian Lumber, National

Lumber Grades Authority (NLGA), New Westminster, BC,

Canada, 2003.

Available from http://www.nlga.org/

43. Standard Grading Rules for Northeastern Lumber, Northeastern Lumber Manufacturers Association (NELMA),

Cumberland Center, ME, 2003.

Available from http://www.nelma.org/

44. Standard Grading Rules for Northern and Eastern Lumber,

National Softwood Lumber Bureau (NSLB),

Cumberland Center, ME, 1993.

45. Standard Grading Rules for Southern Pine Lumber, Southern

Pine Inspection Bureau (SPIB), Pensacola, FL, 2002.

Available at http://www.spib.org/about-us/publications

46. Standard Grading Rules for West Coast Lumber, West Coast

Lumber Inspection Bureau (WCLIB), Portland, OR, 2004.

Available from http://www.wclib.org/

47. Standard Specifications for Grades of California Redwood

Lumber, Redwood Inspection Service (RIS), Novato, CA,

2000.

Available at http://www.calredwood.org/

48. Standard Specifications for Highway Bridges, American

Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

(AASHTO), Washington, DC, 1987.

More recent version is available at http://bookstore.transportation.org/

49. Western Lumber Grading Rules, Western Wood Products

Association (WWPA), Portland, OR, 2005.

Available at http://www.wwpa.org/

50.Design Manual for TECO Timber Connectors Construction,

TECO/Lumberlok, Colliers, WV, 1973.

51. Technical Report 12 General Dowel Equations for Calculating

Lateral Connection Values, American Wood Council (AWC), Washington, DC, 2015.

Available for download.

52. Timber Construction Manual, American Institute of Timber

Construction (AITC), John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

Available at https://www.aitc-glulam.org

53. Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material, General Technical Report 113, Forest Products Laboratory, U.S.

Department of Agriculture, 1999.

Available at http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fplgtr/fplgtr113/fplgtr113.htm

54. ASTM Standard D 2915-03, Standard Practice for Evaluating

Allowable Properties for Grades of Structural Lumber,

ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2003.

Available at http://www.astm.org/

55. ASTM Standard D 5457-04, Standard Specification for Computing the Reference Resistance of Wood-Based Materials and Structural Connections for load and Resistance Factor Design, ASTM, West Conshohocken, PA, 2004.

Available from http://www.astm.org/

ANSI/ASME Standard B18.2.1-1996, Square and Hex

Bolts and Screws (Inch Series), American Society of Mechanical

Engineers, New York, NY, 1997.

Available from the ASME website.

The provisions for calculating bending deflection in the National Design Specification (NDS®) for Wood Construction Section 3.5 increase the long-term deflection with a creep factor, Kcr. The creep factor ranges from 1.5 – 2.0. These NDS design provisions relate specifically to estimating total deflection including the effects of long-term loading.

The deflection limit for the D+L load combination only applies to the deflection due to the creep component of long-term (dead load) deflection plus the short-term (live load) deflection. For wood structural members that are dry at time of installation and used under dry conditions, the creep component of the long-term deflection can be estimated as the immediate dead load deflection resulting from 0.5D. For wood structural members at all other moisture conditions, the creep component of the long-term deflection is permitted to be estimated as the immediate dead load deflection resulting from D. These assumptions are consistent with the creep component of long-term deflection in the NDS Section 3.5.

Deflection limits for the D+L load combination in IBC Table 1604.3, were taken from the legacy Uniform Building Code (UBC) deflection limits. However, the intent of the UBC limits was not brought forward with the provisions. The original intent of these provisions was to limit the total deflection based on the combination of live load deflection and the creep component of the dead load deflection. As a result, there have been several prior code cycle modifications to these provisions to re-instate the original intent, such as the addition of footnote “g” for steel structural members which effectively excludes steel from checking for the creep component of dead load deflection. As currently written and formatted, the D+L deflection provision can be misinterpreted to suggest that the total deflection due to dead load, D, including both the immediate and creep components of the dead load deflection, should be used with the deflection limit in this column. Additionally, use of 0.5 D in footnote “d” is potentially non-conservative without clarification that the 0.5D load reduction approach is only applicable to calculating theD+L deflection for use with the deflection limits in IBC Table 1604.3. As a result, AWC has submitted a change to Table 1604.3 footnote “d” to clarify these points and to make the 2015 IBC Table 1604.3 provisions consistent with the provisions in NDS 3.5.2 for long-term loading, with the stated intent in the UBC, and with similar provisions in ACI 318 as described in the ACI 318 Commentary.

According to the 2005 NDS in section 3.2.3:

3.2.3.1 Bending members shall not be notched except as permitted by 4.4.3, 5.4.4, 7.4.4, and 8.4.1. A gradual taper cut from the reduced depth of the member to the full depth of the member in lieu of a square cornered notch reduces stress concentrations.

3.2.3.2 The stiffness of a bending member, as determined from its cross section, is practically unaffected by a notch with the follow dimensions:

notch depth = (1/6)(beam depth)

notch length = (1/3)(beam depth)

See 3.4.3 for the effect of notches on shear strength.

Changes from the 1997 NDS to the 2005 NDS include addition of the squared component on the strength reduction term and reformat of the shear question in an “allowable shear” format versus the “actual shear stress” format in the 1997 edition.

Also, see the 1997 NDS Commentary for additional information on changes.

Check out our eCourses for “Designing with the NDS.”

There are no published values for shear capacities perpendicular to grain, however, compression perpendicular to grain design values are tabulated in the NDS supplement.

For more information on shear perpendicular to grain, contact USDA Forest Products Lab.

Review of ASTM procedures used to establish allowable shear stresses revealed that shear values were being reduced by two separate factors for effects of splits, checks, and/or shakes. One of these adjustments was made to the base value, while the other was an adjustment to design values for grade effects. In 2000, ASTM standard D245 was revised to remove one of these adjustments, which resulted in an increase of nearly two for allowable shear design values; however, grade effect adjustments were eliminated.

In the 2001 NDS Supplement, shear design values for sawn lumber are generally 1.95 times higher than values printed in the 1997 edition in response to the change in ASTM D245. With this change, shear-related provisions in the NDS were reevaluated and modified where necessary to provide appropriate designs. Changes include:

- Removal of the shear strength increase factor, CH, which previously permitted shear design values to be increased based on limited occurrences of splits, checks, and shakes.

- Revised provisions for ignoring shear loads near supports.

- Revised provisions for shear strength at notches (where permitted).

- Revised provisions for shear strength at connections less than 5d from member ends.

There is a paper on the AWC website, outlining this change in more detail, at the following link: NDS 2001 Changes Overview

Southern Pine is a US species with design values included in Table 4B of the NDS Supplement. Southern Pine from Argentina is included table 4F of the NDS Supplement. Contact the Southern Pine Inspection Bureau for more information: http://www.spib.org.

No. The published Southern Pine timber values are for wet and dry use. The Southern Pine grade rules, section 164.4 state:

“Where lumber is over 4″ thick, the stress ratings apply without regard to seasoning, and stress ratings as herein indicated for a moisture content over 19% apply also to seasoned lumber if over 4″ thick.”

First check Table 2.1 – List of Sawn Lumber Species Combinations beginning on page 4 of the NDS Supplement. Design values for the species listed in the NDS Supplement are provided by the grading agencies.

The 2005 NDS supplement (and subsequent editions) Table 4F has non-North American visually graded dimension lumber including:

Austrian Spruce—Austria and the Czech Republic

Douglas Fir/European Larch—Austria, Czech Republic, Bavaria (Germany)

Montane Pine—South Africa

Norway Spruce—Estonia, Lithuania, Finland, Germany, NE France, Switzerland, Romania, Ukraine, Sweden

Scots Pine—Austria, Czech Republic, Romania, Ukraine, Estonia, Lithuania, Finland, Germany, Sweden

Silver Fir—Germany, NE France, Switzerland

Southern Pine—Misiones Argentina

As for other foreign species such as mahogany, ipe, greenheart, etc., or domestic species such as ash, locust, magnolia, walnut, etc., there is some design information in the Wood Handbook published by the US Dept of Agriculture Forest Service, which can be found at the FPL website. However, since these values are average unadjusted ultimate values, they need to be adjusted per applicable ASTM standards, such as ASTM D245, to arrive at allowable properties. A further complication is that if lumber is not grade stamped in accordance with American Lumber Standard Committee (ALSC) rules (http://www.alsc.org/), there is no way of knowing what type of product will be used in construction. Engineering judgment will be required to use these types of foreign species in structural applications.

Please contact the supplier for more information.

The short answer to this question is that, in general, engineered wood products and assemblies do not exhibit well-defined plastic characteristics. While some material properties show nonlinear stress-strain behavior (e.g., compression perpendicular to grain) as do many types of dowel-type wood connections, they do not exhibit the extended plastic region exhibited by mild steel. Neither do engineered wood products generally exhibit “transition” failure modes such as those of reinforced concrete (i.e., concrete cracking, load redistribution, etc.). As new engineered wood and non-wood composite products are developed and marketed that DO exhibit well-defined plastic characteristics, we hope to extend some of the classical plastic analysis techniques to these products in our LRFD documents.

Chapter 16 of the National Design Specification (NDS) for Wood Construction provides a code-recognized approach for determining the fire resistance of solid sawn, glulam, and select structural composite lumber (SCL) materials, including laminated veneer lumber (LVL), parallel strand lumber (PSL), laminated strand lumber (LSL), and cross-laminated timber (CLT). Design for Code Acceptance Document 2, titled “Design of Fire-Resistive Exposed Wood Members” (DCA 2) provides resources for users to calculate fire resistance for exposed wood members, in compliance with Chapter 16 of the NDS including flexural members (beams), compression members (columns), and solid lumber including decking and other structural members. Additional information including background, examples, and tables providing allowable load ratios for different member types and sizes can be found in Technical Report 10 (TR10).

See also:

The 2015 National Design Specification for Wood Construction (NDS) Chapter 16 and Technical Report 10 allows for the design of wood members exposed to fire.

Carriage bolts (now known as round head bolts) do not conform to ANSI/ASME B18.2.1 Square and Hex Bolts and Screws, so the installation provisions in 2015 NDS 12.1.3.1 (2012 NDS 11.1.3.1) do not apply. Also, carriage bolt dimensions do not comply with the dimensions in ANSI/ASME B18.2.1, therefore, NDS tabulated values do not apply. However, the use of carriage bolts is permissible in accordance with 2015 NDS 11.1.1.3 (2012 NDS 10.1.1.3) provided that characteristics of the carriage bolt are accounted for in connection design and installation. These characteristics include carriage bolt material, bending yield strength (Fyb), diameter, and the potential presence of a square neck under the head in lateral calculations and installation instructions. ASME B18.5-2012 Round Head Bolts provides standard dimensions as shown in Tables 1 and 2 for round head and round head square neck bolts, respectively.

Tables 1 and 2 reprinted from ASME B18.5-2012 Round Head Bolts (Inch Series), by permission of The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. All rights reserved.

The 2018 National Design Specification® (NDS®) for Wood Construction is the first edition to specifically address the withdrawal strength of smooth shank stainless steel nails. The new stainless steel nail withdrawal equation produces lower values of withdrawal strength than the NDS steel wire nail equation based on tests of smooth shank carbon steel wire nails. The reduction in withdrawal strength, due to the reduced friction provided by stainless steel, varies 5% to 40% over a common range of wood-specific gravity with the greatest reduction associated with high-specific-gravity wood.

AWC has links to historic documents on our website here: NDS Archives

Designers can view and download copies of the 1922 Design Values for Structural Timber and the 1944 NDS on this page. Archive versions of the NDS are also available for a small fee.

Ecourses are also available relating to evaluating in-service structures. Both DES140 – Structural Condition Assessment of In-Service Wood and DES160 – Evaluation of Recommended Allowable Design Properties for Wood in Existing Structures can provide helpful information to professionals working with existing structures.

See also General FAQ, “Where can I find information on evaluation, maintenance, and repair of existing structures?”

The sections of the IBC and IRC that deal with sound transmission are IBC Section 1206 and IRC Appendix AK. These code provisions apply to wall and floor/ceiling assemblies separating dwelling units from other dwelling units, or from adjacent public areas, within a building. These provisions do not deal with sound transmission from outdoors to indoors, through an exterior wall. Although US model building codes do not contain provisions regulating minimum sound transmission performance of exterior walls, there are some cases where designers specify a minimum level of sound transmission performance for exterior walls on specific construction projects. In such cases, the most direct and accurate way of assessing sound transmission performance of an exterior wall is through field testing in accordance with ASTM E966 and analysis in accordance with ASTM E1332. The single-number ratings resulting from this test and analysis procedure are outdoor-indoor transmission class (OITC) and outdoor-indoor noise isolation class (OINIC(θ)). Conversely, sound transmission class (STC) is determined through laboratory testing in accordance with ASTM E90 and analysis in accordance with ASTM E413. This testing and analysis is most commonly used for assessing the sound transmission performance of interior walls and floor/ceiling assemblies separating dwelling units from other parts of a building, as these are the only places where US model building codes require minimum sound transmission performance. While it is possible to perform an ASTM E90 test on an exterior wall assembly in a laboratory and determine an STC rating for that assembly using ASTM E413, this is less commonly done because building codes do not place minimum performance requirements on sound transmission through exterior wall assemblies and because OITC and OINIC(θ) ratings provide in-situ assessments of exterior wall performance.

As stated in Section 1.1 of ASTM E90, the scope of this standard is limited to building partitions such as walls, operable partitions, floor-ceiling assemblies, doors, windows, roofs, etc. Although it is possible to use ASTM E90 to assess the sound transmission performance of individual components that would be used within an assembly, such use is not within the scope of the standard and is typically only done for the purpose of research. Furthermore, sound transmission class (STC) values derived for individual components of an assembly are not necessarily additive. In other words “component-additive methods” (CAM) do not necessarily yield accurate estimates of sound transmission through a complete assembly. This is especially the case when dealing with assemblies that have a cavity or void through the thickness (e.g., a stud wall with cavities between the studs). That said, there are other models (besides CAM) for estimating sound transmission performance that yield more accurate results. For example, AWC’s Technical Report 15 (TR15) provides models that can be used to estimate STC and impact-insulation class (IIC) ratings for light-frame floor/ceiling assemblies (https://awc.org/publications/tr-15-calculation-of-sound-transmission-parameters-for-wood-framed-assemblies).

2012 International Residential Code (IRC) States:

R501.3 Fire protection of floors. Floor assemblies, not required elsewhere in this code to be fire resistance rated, shall be provided with a ½ inch gypsum wallboard membrane, 5/8 inch wood structural panel membrane, or equivalent on the underside of the floor framing member.

Exceptions:

- Floor assemblies located directly over a space protected by an automatic sprinkler system in accordance with Section P2904, NFPA13D, or other approved equivalent sprinkler system. (AWC has developed a guide for partial sprinklering of unfinished basement areas.)

- Floor assemblies located directly over a crawl space not intended for storage or fuel-fired appliances.

- Portions of floor assemblies can be unprotected when complying with the following:3.1 The aggregate area of the unprotected portions shall not exceed 80 square feet per story.

3.2 Fire blocking in accordance with Section R302.11.1 shall be installed along the perimeter of the unprotected portion to separate the unprotected portion from the remainder of the floor assembly.

- Wood floor assemblies using dimension lumber or structural composite lumber equal to or greater than 2-inch by 10-inch nominal dimension, or other approved floor assemblies demonstrating equivalent fire performance.

The genesis for this requirement was five separate code change proposals introduced in 2009 to revise IRC. The IRC Code Development Committee disapproved all the proposals and requested that the interested parties work together to develop a public comment. In October 2010, the ICC membership approved the above text, jointly developed by the International Association of Fire Fighters, International Association of Fire Chiefs-Life Safety Section, the National Association of Home Builders, and the American Wood Council.

Q: Do I have to specially fire block the perimeter of the opening between the permitted 80 ft² unprotected area and the balance of the protected area?

A: Recent testing with an 80 ft² unprotected area has shown that if a fire occurred under a protected area, fire blocking would provide a minimal level of performance of the membrane system. This affirms the proponents’ intent that the perimeter between the 80 ft² unprotected area and the protected area needs to be fire blocked and no special treatment beyond the specified fire blocking is necessary to achieve the desired performance.

Q: Do I have to treat the joints in the gypsum wallboard with tape and compound?

A: Gypsum wallboard joints are not required to be finished with tape and joint compound. A somewhat analogous requirement in the code is a thermal barrier over foam plastic insulation. Such barriers are also not required to be finished with tape and joint compound. Likewise joints between wood structural panels are not required to be finished with wood filler and sanded.

Q: What was the intent when Clause R501.3, Exception 4 (R302.13 in the 2015 IRC) was developed?

A: As one of the original proponents of this language, AWC has insight into the intent and discussions leading to development of the wording in this exception.

To be considered equivalent to 2×10 sawn lumber or SCL, the framing members should support a load corresponding to 50% of the full bending design of the framing members, while being subjected to an ASTM E 119 time/temperature heating regime. All components utilized in the manufacture of the framing members (fasteners, plates, hardware, etc) should be utilized during testing. The test end criteria should be structural member failure.

AWC believes that the most straightforward and accurate means of determining the required minimum fire resistance time would be to estimate that time using the calculation methodology specified in NDS Chapter 16 for unprotected solid-sawn 2×10 floor joists assuming: a 3-sided exposure, a nominal char rate of 1.5 inches/hr, a bending strength to ASD ratio of 2.85, and supporting a load corresponding to 50% of full bending design.

Q: Do trusses of 2 inch nominal by 10 inch nominal dimension fall within the intent of Exception 4 to Section 501.3 in the 2012 IRC?

A: No. The International Code Council has issued an advisory opinion that Exception 4 does not apply to trusses. Further, the supporting information submitted with the original code change proposal for this section identified where basic membrane protection was to be required and specifically cited unprotected floor/ceiling assemblies using trusses, I-joists, cold formed steel members, and bar joists as structural members needing to meet the membrane requirements. Additionally, the ICC advisory opinion states that assemblies using wood trusses may be approved for exemption if the floor assembly demonstrates equivalent fire performance to floor assemblies using 2×10 lumber. While not noted in the ICC advisory opinion, any other framing system may be approved under Exception 4 by demonstrating equivalent fire performance to floor assemblies using 2×10 lumber.